Sunday, 1 April 1945

Greater Berlin (...) forms a single camp

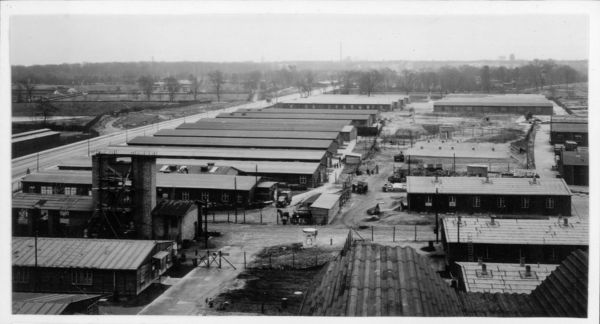

"At that time Berlin was covered with wooden barracks ... In every gap, however small, in the megalopolis, flights of brown spruce wood blocks covered with tar paper had nested. Greater Berlin, that is, Berlin and its suburbs, forms a single camp, a camp that stretches for miles, crumbling between the permanent buildings, the monuments, the office blocks, the train stations, the factories."

This is how François Cavanna, the former French forced laborer and later co-founder of the satirical magazine "Charlie Hebdo", described the situation in Berlin after the war.

There were about 3,000 collective accommodations throughout the city. When Berlin capitulated to the Red Army on 2 May 1945, there were about 370,000 forced labourers from all over Europe in the city. Most of them had been deported to Germany against their will. They worked in the armaments industry, in small and medium-sized enterprises of all kinds, for the churches, the magistrate and the districts, in private households.

While before the Second World War forced labour was used primarily as a means of discrimination and persecution against certain population groups, such as Jews, Sinti/Sintezza, Roma/Romnija and as "asocial" discriminated against, in the course of the war more and more "civilians" from all over Europe were deported to Berlin for forced labour.

Many forced labourers in Berlin experienced the spring of 1945 as liberation. Most Western European civilian workers were able to return home in the summer of 1945. A large number of former "Ostarbeiter", however, had to undergo extensive interrogations in so-called "testing and filtration camps" of the Soviet secret service. Quite a few were deported to penal camps. Others were recruited by the Red Army into its own ranks on the spot.