Videos

Video Messages

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the end of the war in spring 2020, the Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Center planned several events with former forced labourers as well as second generation family members. Due to the pandemic, the anniversary celebrations had to be canceled. But we asked our guests to record a video message. Here, six of our guests, talk about the importance and consequences of the liberation in 1945. For themselves, for their parents and for their families, until today. We would like to thank everyone involved very much for their contributions.

-

1

April

1Sunday, 1 April 1945

Greater Berlin (...) forms a single camp

"At that time Berlin was covered with wooden barracks ... In every gap, however small, in the megalopolis, flights of brown spruce wood blocks covered with tar paper had nested. Greater Berlin, that is, Berlin and its suburbs, forms a single camp, a camp that stretches for miles, crumbling between the permanent buildings, the monuments, the office blocks, the train stations, the factories."

This is how François Cavanna, the former French forced laborer and later co-founder of the satirical magazine "Charlie Hebdo", described the situation in Berlin after the war.There were about 3,000 collective accommodations throughout the city. When Berlin capitulated to the Red Army on 2 May 1945, there were about 370,000 forced labourers from all over Europe in the city. Most of them had been deported to Germany against their will. They worked in the armaments industry, in small and medium-sized enterprises of all kinds, for the churches, the magistrate and the districts, in private households.

While before the Second World War forced labour was used primarily as a means of discrimination and persecution against certain population groups, such as Jews, Sinti/Sintezza, Roma/Romnija and as "asocial" discriminated against, in the course of the war more and more "civilians" from all over Europe were deported to Berlin for forced labour.Many forced labourers in Berlin experienced the spring of 1945 as liberation. Most Western European civilian workers were able to return home in the summer of 1945. A large number of former "Ostarbeiter", however, had to undergo extensive interrogations in so-called "testing and filtration camps" of the Soviet secret service. Quite a few were deported to penal camps. Others were recruited by the Red Army into its own ranks on the spot.

- 2

-

3

April

3Tuesday, 3 April 1945

„Normality“ until the end?

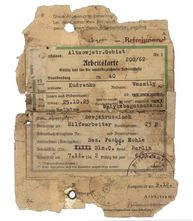

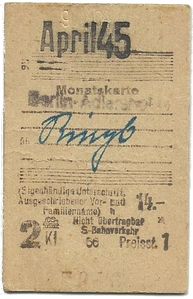

In the winter and spring of 1945, too, numerous forcedlaborers were on the move throughout the entire Berlin city area, despite continuing air raids and the steadily approaching front. Various eyewitness reports and documents bear witness to this. For example, a pass for using the Berlin S-Bhn from January 1945 and a monthly pass for April 1945, issued at the Adlershof S-Bahn station. They belonged to the Italian forced laborer Ettore Gorla, who had to work for AEG and in road construction. Together with 400 other Italians, he was interned in the GBI camp 75/76 (now the Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre). Gorla had marked the location of his camp in the city with a pencil on this map of the Berlin S-Bahn and U-Bahn network.

In March and April 1945, public transport was hardly reliable. Due to the numerous bomb hits, Berlin's infrastructure was so severely limited that many forced laborers had to walk miles to their workplaces.

They were almost defenceless against the air raids and detonations of the last months of the war. Public and company-owned air-raid shelters were reserved for the Berlin population or German employees. Most camps did not have their own air-raid shelters.

Although the destruction caused by Allied bombing raids severely affected the city, many forced laborers were forced to appear at their workplaces until the very end. Quite a few experienced the liberation at their place of work. - 4

- 5

- 6

-

7

April

7Saturday, 7 April 1945

Duty at the risk of death

The last months of the war were marked by signs of disintegration, but also by the increasing danger to life from the air raids. Approximately 14,000 people were constantly engaged in air-raid protection in the imperial capital. It is hardly known that many of them were forced labourers.

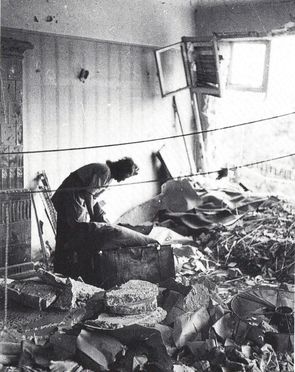

Civilian forced labourers, prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners were used to remove rubble after bomb hits or to defuse unexploded ordnance. They also had to dig up buried persons and bury corpses. Some of the forced labourers even wore the blue or grey uniforms of the "Technische Nothilfe" - they were supposed to replace the Berlin "Nothelfer" (emergency helpers) who were meanwhile deployed at the front.

In the last weeks of the war, more and more forced labourers had to help dig trenches and erect tank barriers, at the risk of their lives. As former forced labourer Euzebiusz Wiktorski reports: "Before the invasion of the RedArmy, the majority of people were sent to dig trenches and do other work outside the factory. Those who remained in the factory dismantled, preserved and sank the better machines in the canal." With a little luck, the forced labourers were able to find food in the rubble, which made this activity seem privileged. At the same time, however, they exposed themselves to the danger of being punished with death as "plunderers".Tags: Belgium - 8

- 9

- 10

-

11

April

11Wednesday 11 April 1945

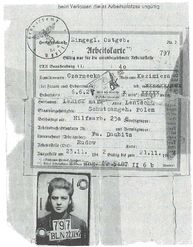

Kazimiera Kosonowska, geb. Czarnecka

Kazimiera Kosonowska, née Czarnecka

"In April, the carpet bombing begins. At a not too high altitude, whole squadrons of planes fly and systematically bomb the city. During an air raid, other factory buildings are destroyed. Dutchmen try to put out the fire and protect the rest of the buildings."

"One sunny day in April, a large group of us and the guard drive directly from the factory into town. With astonishment we discover that we arrive at a large and beautiful Charlottenburg cemetery. Dozens of coffins are standing on the carefully maintained paths, waiting for burial; they are the victims of the latest attacks. The cemetery staff shows us the places, and we are forced to dig the graves."

"Chaos and panic breaks out among the Germans. For a few days now, in a hurry, day and night, countless columns of military cars and other heavy vehicles have been driving by. You can hear the constant hum of the engines. In the streets you can see older men and very young boys ready to defend the city. After the panic-like retreat of the German troops, it suddenly becomes quiet. There is a strange calm, like before the storm, which lasts all day long."

(Letter from the former forced labourer Kazimiera Kosonowska to the Berlin History Workshop).

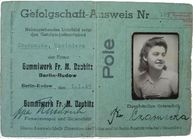

Kazimiera Czarnecka helps her father in the forge after finishing primary school. A longer school attendance is not possible, because the German occupying forces have closed all secondary schools. On 14 November 1942 she has to report to the German employment office under threat of a penalty for the whole family. At the age of 18 she is deported from there directly to the German Reich. In the transit camp in Berlin-Wilhelmshagen, a representative of the "Gummiwerk Fr. M. Daubitz" company, Kazimiera Czarnecka, chooses Kazimiera Czarnecka as a forced labourer. She is taken to a collection camp in Berlin-Adlershof, which had previously been occupied by prisoners of war. From there, Kazimiera Kosonowska has to walk 1.5 kilometres every day to the rubber factory of the Daubitz company, where she works under the most difficult conditions in the production of rubber gloves for the Wehrmacht.

At the end of the year, the company's staff moves to a camp in Köpenicker Strasse in Rudow. Kosonowska works 10 hours a day, there is no medical care in the camp. Like all Polish forced laborers, she has to wear the "P" badge on her clothes, always visible. After all the deductions, hardly anything remains of her supposed wage. In May 1943 Kosonowska makes friends with young Poles from a camp in Grünau. This friendship promotes her will to self-preservation.During the ever-increasing air raids, Kosonowska tries to protect herself and other forced laborers in trenches covered with wooden boards behind the barracks. In a letter to the Berlin History Workshop, she impressively describes the last months and weeks before the liberation.

- 12

- 13

-

14

April

14Saturday, 14 April 1945

Violence against forced labourers at the end of the war

While defensive installations are being erected in Berlin in great haste, Soviet troops are already standing west of the Oder. In view of the looming defeat, the situation for the forced labourers becomes even worse. Numerous foreign workers and innumerable concentration camp prisoners fall victim to the murderous violence of the last weeks of the war by the Gestapo, SS, Wehrmacht, and in some cases by units of the "Volkssturm".

An order issued by "Reichsführer SS" Heinrich Himmler on April 14, 1945 to the commanders of the concentration camps and heads of the prisons, which is often described as the prelude to the "death marches", has become known: No prisoner may fall alive into the hands of Allied troops. Even if Himmler's central order to murder concentration camp prisoners and foreign forced labourers cannot be proven - at least not in writing - the evacuations of the camps and prisons in and around Berlin are also repeatedly accompanied by massive violence and even targeted executions. Tens of thousands of concentration camp inmates, prisoners of war and forced labourers are set in motion from Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück and other camps in western direction shortly afterwards. Shortly before the end of the war, the SS clears prisons, such as the Gestapo's house prison in Berlin's Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, and executes the inmates.

Fear of resistance and revenge actions by the civilian forced laborers and escaped prisoners is widespread among the Nazi leadership and the German civilian population. In Berlin, there are repeated violent actions against foreign workers. The former French forced laborer François Cavanna reports: "With our stomachs tightened, we set off again to our wretched construction site. It is located in the Uhlandstraße area. (...) They have rammed roof beams into the rubble. They've tied three girls and a guy to it. Russians. They fired a bullet into each other's necks. Their smashed heads are hanging on their chests."

-

15

April

15Sunday, 15 April 1945

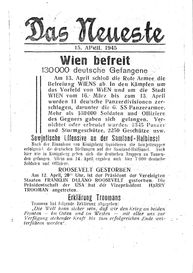

"Paper War" over Berlin

Throughout the war the dropping of leaflets over "enemy territory" was an important part of psychological warfare. In the last weeks of the war, the Allied forces dropped thousands of leaflets over the Berlin city area. In these leaflets, they call on German soldiers to surrender or defect and urge the civilian population to stop work, seek protection and offer resistance.

Described as "enemy propaganda", the possession and above all the passing on of such leaflets is strictly forbidden and can be punished with prison or death.

The leaflet dated 15 April 1945 was owned by the former Polish forced labourer Józef Przedpełski. Przedpełski is deported to Berlin in September 1944 with his pregnant wife Anna from Łódź. There they both have to work in the Reichsbahn repair works in Schönweide (Adlergestell 153-43): "These leaflets were dropped from planes over Berlin," Przedpełski reports in a letter. "They were intended to break the spirit of resistance of the German soldiers, and on that occasion encouraged the 'Ostarbeiter'."

Shortly before the end of the war, Allied planes also drop leaflets aimed directly at prisoners of war and civilian forced laborers. With slogans such as "Foreign workers: discipline accelerates the return home" or "Keep order and discipline", the aim is to prevent chaos, looting and violence by liberated forced laborers.

Tags: Przedpełski -

16

April

16Monday, 16 April 1945

"Battle of Berlin"

Start of the large-scale offensive on Berlin. At the Seelower Heights, 1 million Red Army men stand at the gates of the "Reich Capital". While the Nazi leadership still propagates the "Final Victory" and drags young and old Berliners to the "Volkssturm", German and foreign civilians have to dig trenches and erect barricades. For many forced labourers in the city there is growing hope that the war will end soon. The former French forced labourer Marcel Elola remembers:

"At a certain moment we knew that the Russians would come. Their hunters fired low level shots into the streets in places... Needless to say, the fear of the Berliners has reached its peak. Everything that the Wehrmacht, the SS and the Gestapo put up with during the last five years came back to them like a boomerang. The surviving Germans believed that they would all be shot, tortured or sent to Siberia. All in all, they were not entirely wrong about this foreboding. When the Russians came, some of them respected the laws of war as little as the Germans had respected yours a few years earlier."

"In early April, 1945, explosions occur all over the city. It is the Russian shells that ravage the capital of the Third Reich. No German will admit it to himself. That's not what they're told on the radio. But for better or worse, one has to face the facts at some point. The Red Army is at the gates of Berlin."

"Many people are killed in the streets on their way to work. "Work" is exaggerated. Let's say that they move like robots to the place where they work, if it still exists. The power supply is cut off at ever shorter intervals. One can no longer work."

(Source: Marcel Elola: "I was in Berlin". A French forced labourer in Germany 1943-1945, Berlin: Divers Gens/Edition Berliner Unterwelten, 2005, p. 88f)

Tags: France - 17

-

18

April

18Wednesday, 18 April 1945

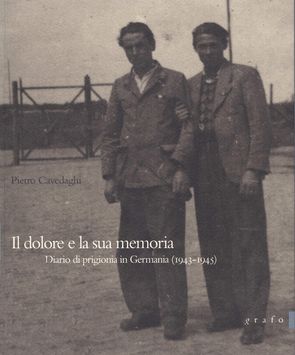

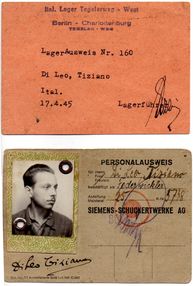

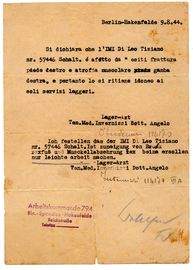

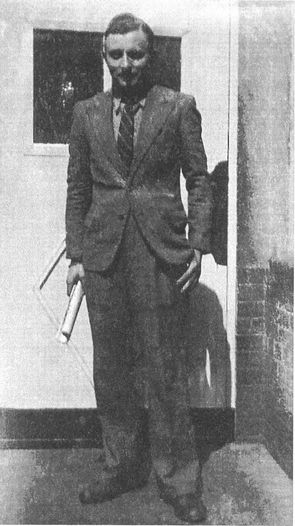

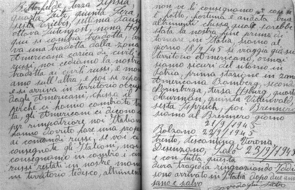

Pietro Cavedaghi - "Siemens Wernerwerke"

"It's mid-April. Life has become terribly hard. The bombing is getting harder and harder. At night, bombing continues for up to six hours, and you can't sleep for even an hour. The Russian cannons can be heard not far away and the Anglo-American planes help them with their deadly fire. So we hope that it really is only a matter of a few more days. You can't even leave the camp for work anymore. In the city everything is interrupted, only German soldiers are still on the trains, retreating from all fronts."

"The Russians are near Berlin. You see hundreds and hundreds of Russian machines pounding on German artillery. One squadron after another. They are constantly hammering at the German troops that have gathered in Berlin and we are here in the city and we are getting the pills [presumably bombs] that are left over from the German gentlemen on our heads. The Russians are trying to blow up all trains that arrive in the city with ammunition. In short, it is clear that we are trapped. The Russians are surrounding the town. Be brave, now it's really a matter of saving your own skin."

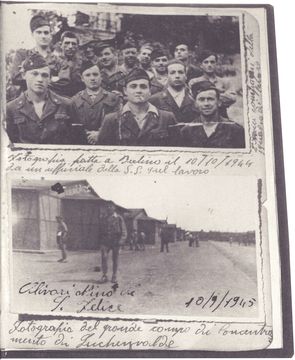

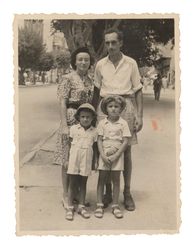

Pietro Cavedaghi was 19 years old when he was captured by the Wehrmacht in Pinerolo on 12 September 1943 and deported to the German Reich. First he was taken to the Luckenwalde transit camp, like thousands of other Italian prisoners, and then to Berlin. He was given the number 115.265.III.A. and was assigned to work at the Siemens-Schuckertwerke in Spandau, where he had to work under the supervision of armed guards. From his camp in Weißensee, Cavedaghi has to take the S-Bahn to work for one hour every day. In September 1944 he is transferred to a camp in Schöneweide, from where he has to walk the long way to work. Shortly before the end of the war he has to rebuild a destroyed post office building as a bricklayer at Schlesisches Tor. Cavedaghi's report on the end of the war is amazingly detailed and impressively illustrates the situation of many forced laborers in Berlin in the spring of 1945.

From the diary of Pietro Cavedaghi: "The pain and the memory. Diary of Imprisonment in Germany (1943-1945), Ital. Original: Il dolore a la sua memoria. Diario di prigionia in Germania (1943-1945,) Grafo 2005."

Tags: Italy - 19

-

20

April

20Friday, 20 April 1945

Wanda Tworkiewicz - Camp Johannisthal

"For Hitler's birthday on April 20, Allied planes came and dropped leaflets over our work sites. A joke was circulating among us at that time: On Hitler's birthday they didn't drop bombs, only leaflets. I didn't see what was written on the leaflets. I only saw how they fell down... A colleague named Schulz had indicated at work in the days before that he also understands Polish. He came from Silesia. He had seen me in this forest, and the next day at work he said to me in Polish, in a Silesian dialect: 'Wanda, have you seen these leaflets? I have.' - 'What does it say?' - 'We should stop. But how can we stop if we're being bombed?"

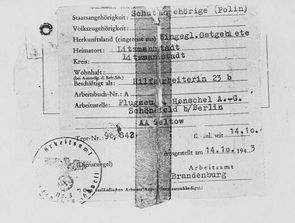

Wanda Tworkiewicz is deported from the Polish city Łódź to Berlin in October 1943. After she is first taken to a transit camp in Brandenburg, she is finally sent to a barrack camp in Berlin-Johannisthal. Here she has to work in the factory of the aircraft manufacturer Henschel. During heavy air raids on the night of Christmas Day 1943, she leaves the burning barracks camp in panic, only covered with a blanket. While the factory remains almost intact, the camp burns down almost completely. Tworkiewicz is then transferred to Schönefeld and must now walk to work every day in Johannisthal. She is liberated on 23.04.1945 in Schönefeld.(Letter from former forced labourer Wanda Tworkiewicz to the Berlin History Workshop. Source: Documentation Centre NS Forced Labour, Berlin History Workshop Collection)

-

21

April

21Saturday 21 April 1945

Königs Wusterhausen: Death march to the north

"Königs Wusterhausen: Death march to the north "When the Russian troops approached Königs Wusterhausen in April 1945, we were all quickly transported to Sachsenhausen. There the image of Ravensbrück was repeated in almost the same cruelty, but the stay here did not last very long. After a short time - we could hear clearly the approaching front and see it glowing in the night as red glow in the sky - all prisoners were ordered to set off. That was the death march. The barracks, it was said, were loaded with explosives and were blown up. But my mother said she had no strength left to go, and that she didn't care where or how she died."

(report by Dr Richard Fagot)Richard Fagot came from an assimilated Jewish family from Łódź. His father was director of one of the biggest rubber factories in Poland. On Fagot's fourth birthday the Wehrmacht invades the country. A little later he has to move with his family to the newly built "Ghetto Litzmannstadt". However, Fagot's family is very lucky to escape deportation to Auschwitz. Together with a few other families, they are selected to produce makeshift homes for bombed-out German families in Königs Wusterhausen. After a stopover in the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen, the family is separated. The father is transferred to Königs Wusterhausen. Fagot and his mother are sent, like the other women, to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where they survive the winter under catastrophic conditions. In February 1945 the surviving Łódźer women and about 30 children are "surprisingly brought out of hell" and brought to Königs Wusterhausen.

Background:

The Königs Wusterhausen concentration camp subcamp, located southeast of the Berlin city limits, was built in 1944 and was located at the goods station, in the eastern part of Königs Wusterhausen (Storkower Straße/Priestergraben). Most of the approximately 600 Jewish prisoners of the camp came from Łódź. When the Łódźer ghetto was closed down, they were held back by the SS for clean-up work and then transferred to Königs Wusterhausen.

The women in the camp had to nail together ammunition boxes for the Krupp company and produce "winter construction boxes" for truck engines from Siemens. The men were employed in the nearby production of makeshift homes.

A few days before the liberation of the camp on April 26, 1945, some of the male prisoners were taken to Sachsenhausen and from there sent on the death march towards Mecklenburg. Among them was Dr. Richard Fagot. Weakened by the exertions, many of the prisoners were shot on the march. A second group, consisting of children and women, had to start the march from the concentration camp subcamp Königs Wusterhausen towards Sachsenhausen between April 18 and 20, 1945. Some of them were liberated by Soviet troops on the way to Sachsenhausen. The guards of the camp fled on April 22 in civilian clothing. The Red Army reached the camp on April 26, 1945. -

22

April

22Sunday, 22 April 1945

Teltow: Nikolaj Fjodorowitsch Galuschkow

"On April 22, all 37 people were taken out. We were counted and tied up. I was tied up with Ulyanchenko. Three more people were brought. So we became 40. Among them was a woman. And an old man, who was not in his right mind. We were taken away very quickly. There was a subway station nearby. I forget what it was called. We came to Friedrichstrasse... People looked at us with horror, we were completely emaciated. Half-skeletons were there... Then we changed trains again. Ostkreuz... Ostbahn... Großbeeren, I remember that."

"There was a very heavy guard until Teltow. We were led on foot ... A barrack. There was an SS unit there, which confronted us. We were positioned in front of the barrack. We only had trousers and a shirt for clothes. But we were searched thoroughly. Some time later one of the troops stepped forward: Quick! Tanks!

Then we had to line up. We clung together. An SS man hit me on the back of the head with the butt of his rifle and I went down. When the shooting began, everyone fell down, instantly. When I came to, there was silence, only the wounded moaning. I lay beside a pile of lifeless bodies and saw the first Russian tank rolling up. The saving Soviet army had reached Berlin."In 1942 Nikolaj Fjodorowitsch Galuschkow is deported from the Russian city Perwomajskij to the German Reich. The 15-year-old is sent as a gravedigger to the "cemetery camp" on Hermannstraße in Neukölln. The forced camp is run by the 42 Berlin parishes. Day after day Galuschkow and his comrades have to dig graves and bury the dead throughout the city. When trying to escape with other members of a resistance group, he falls into the hands of the Gestapo. Galushkov is taken to the Gestapo house prison in Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, where he and 30 other prisoners are sentenced to death by firing squad after two months in prison, torture and interrogation.

On April 22, SS men take Galuschkow and his fellow prisoners by S-Bahn to Teltow, on the southern outskirts of Berlin. When the firing squad opens fire on the crowded group, Galuschkow is buried under the bodies of the others. He survives the murder at the last second, when Soviet tanks suddenly arrive - the Gestapo pulls out before Galushkov is even hit by the shots.

Immediately after the liberation, the Soviet military conscripts Galushkov to do his military service. Later he moves to Komi in the Arctic Circle, then to Orel near Moscow. He works as a locomotive heater and engineer.Sunday, 22 April 1945

Heinersdorf: "At 4 pm we had regained our freedom"

"April 22 was a Sunday and a warm and sunny day. The roar had come much closer, allegedly the Russians were already 20 km away from us. The inhabitants of Osdorf gathered in front of their houses, they talked excitedly. Some carts were being prepared to head west, before the Russians surrounded Berlin. I had an afternoon off that day and hurried to get to Heinersdorf. I left my suitcase in the cellar. I just wanted to tell Frau Müller that I was leaving. As I had to pass the bathroom, I noticed that it was burning in the bathroom stove. Why had the miller lit the stove? I went inside. The stove door was open, and next to the stove, leaning against the bathtub, stood the empty frame of the large Hitler painting that had hung in the place of honor in the living room... I found Frau Müller on the way outside the house. She did not reply to my words that I was going to Heinersdorf. I left quickly - and never saw her again."

"From the early morning, everyone lived in great excitement. The Poles employed in Heinersdorf wanted to welcome the Russians in a dignified manner. The evening before they had persuaded old Ciesielska to sew a Polish flag on her hand sewing machine. In the morning they crept up the tower of the manor house and hung the flag on the mast. At 10 o'clock the Germans discovered the flag, but none of them had the courage to climb up the tower and take it down. Only the gendarme arrested Zdisiek Ciesielski, the main culprit. They didn't know what would happen to him. They said they would shoot him. But they couldn't do that anymore because the shooting was so close..."

"Suddenly some German soldiers ran along the house, sweaty and out of breath, then some more called for water, and suddenly we heard Russian calls. Again a sharp shooting broke out, this time right behind us, next to the barn, and two Soviet soldiers rushed into our apartment. They quickly asked for the Germans and ran on.

On April 22nd, at 4:00 p.m., we had regained our freedom."Background:

In May 1941, Ludomiła Szuwalska was torn from her sleep in her Polish homeland by German gendarmes and sent to the German Reich for forced labor. She is first sent to a collection camp in northeastern Berlin. A few days later the family is taken to work in agriculture on a farm in Heinersdorf, south of the Berlin city limits. Once owned by a Jewish family, the estate complex was expropriated after 1933 and handed over to the Berlin city administration. Several Polish families already work there and live together in a very confined space. In June 1942, Szuwalska was separated from her family and moved to the farm of the Müller family, openly convinced of National Socialism, in neighbouring Osdorf

clever. Here she has to live without heating in a tiny attic room and work in the house and in the garden. -

23

April

23Monday, 23 April 1945

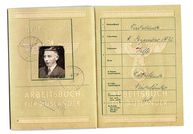

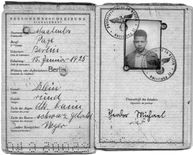

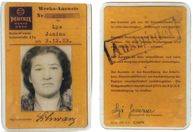

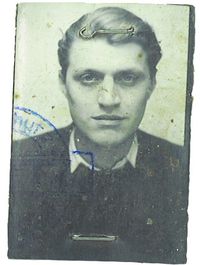

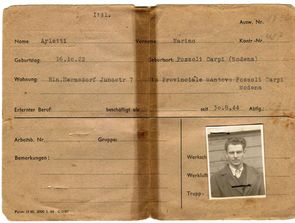

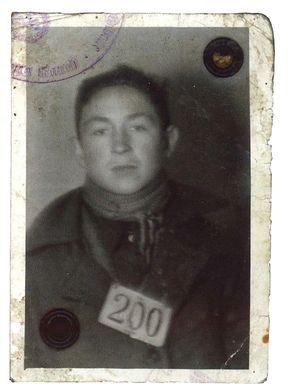

Hermsdorf: Identity card of the forced labourer Marino Arletti

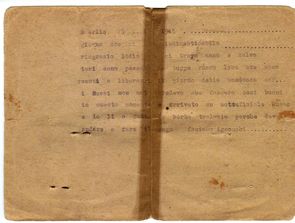

On April 23, Soviet troops from the north advance to Berlin-Tegel, where they engage in three days of fighting with a factory security battalion. Meanwhile, individual units bypass the area via Waidmannslust, Wittenau and Hermsdorf. Here the 22-year-old Italian forced laborer Marino Arletti is freed. In a note on the back of his identity card he records:

"Berlin, 23. 4.1945. A day I will never forget. I thank God that I am healthy and safe. Yesterday the Russian troops arrived, they came to liberate us. I never thought they would be so good. A Russian sergeant came to me and I made his beard. But enough of that, I have to go and prepare the sauce ... we are cooking gnocchi."

Montag, 23 April 1945

Tegel: Liberation of Jean René

Jean René was born as the child of a farming family in 1905 in Bazas in the Gironde. Working as a carpenter, he was drafted by the French military for artillery in 1939. On June 18, 1940, German units capture him near Paris and take him and other prisoners to Stalag IIID near Berlin. As a prisoner of war he has to work hard in Berlin, first in a waterworks, then in a shed at Grünau station, then for cement work at the Rohmberg company. From the camp in Grünau, René is transferred to Mariendorf. He makes his way to work every day by underground. In November 1944, he is transferred again, this time to a camp in Berlin-Tegel. René now worked for a carpentry workshop. Jean René writes vividly about his experiences in Berlin and his liberation in his diaries, which are only found many years later by his son Hervé:

"I had a pretty good night's sleep, despite the constant shooting. No work today: I think that the work at the brick works is over. Last night, the boss came to say goodbye; he had tears in his eyes. The tone of voice has changed over the five years. It is sad, despite everything, because here it is like everywhere else: there are good people, who unfortunately are not in the majority, and it is they who suffer.

It is 8 o'clock. I will sleep in the bunker, because the bullets are coming from all sides, it is not a good idea to sleep in the barrack! This morning I thought I saw the Russians at Tegel, but it's still thundering. It's true that it's not yet evening...I had to stop writing this morning when at eight o'clock, just when I least expected to be liberated today, the first Russian soldiers passed by. We saw infantrymen first. I can't express in words how happy we have been since 8 o'clock this morning, because not far behind the infantry came tanks and hundreds more. All the foreigners are on the sidewalks and the joy is written all over their faces. The Germans are hiding in the houses; many vehicles have stopped to give us cigarettes and bread."

(Source: "A plaything in the turmoil of war. Diary of a prisoner of war," edited by Hervé René, Saint-Denis: Edilivre, 2017)

-

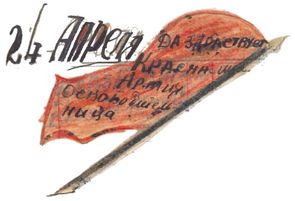

24

April

24Tuesday, 24 April 1945

Lichtenberg: Umberto Palo and Rosemarie Heinze

"All the bunker doors were firmly locked and secured. Outside, the battle raged. It went on. From mouth to mouth it spread: The Russians are here! On the calendar it said: 24 April 1945. So now the time had come: Everyone seemed very calm - very quiet. In the lock chamber, the few men with the bigger boys worked like hardworkers on the wheel of the air supply system, which could be turned in an emergency. I think they saved us from suffocating to death.

(Memoirs of the Berliner Rosemarie Erdmann, née Heinze; http://www.kindheit-und-politik.de/)

As a young girl Rosemarie Heinze was enthusiastically involved in the "Bund Deutscher Mädels" (BDM). As befitted a member of the Nazi youth, she collected raw materials for victory from door to door. After the outbreak of the war, her attitude soon changed: Again and again she observed how a train of miserable characters passed by almost daily from the notorious "Arbeitserziehungslager Wuhlheide" (Work Education Camp) in Friedrichsfelde - a sight she will never forget. When Soviet troops reach Berlin, Rosemarie Heinze experiences traumatic rapes by Russian soldiers. A liberated forced laborer from Italy becomes her protector: Umberto Palo, from the meat factory in Lichtenberg Triftweg where Rosemarie's father had his workplace. For several weeks Palo and other liberated Italians provide the family with food. From the liberation until his return to Italy, Umberto Palo remained a close friend of the Heinze family. 15 years later Rosemarie Erdmann visits him together with her husband in Battipaglia near Salerno.

(Source: Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center)

Tuesday, 24 April 1945

Neukölln: "Long live the Great Red Army!"

"Long live the Great Red Army, our liberation army!

This day is the happiest day, you might say, in my young life. I, a seventeen-year-old boy, was deported to Germany under force, condemned to suffering and grief. The Red Army liberated us in the end. Now I can return home, now I can breathe home air with my full chest in and out. I will work freely for my country.

When the conquest of Berlin began, the skies were filled with Soviet planes. The fascists entrenched themselves very well. I was with a friend in a hiding place near our barracks. The fighting was fierce... The Germans were still shooting with machine guns from the neighboring houses. But the battle was already won by and large. Now I saw the Red Army's strength with my own eyes... Now we are among compatriots. I was so happy! I started to cry."

(From the diary of the former forced laborer Wasyl Timofeyevich Kudrenko)Vasyl Timofeyevich Kudrenko is 16 years old when he is deported from a Ukrainian village to Berlin in 1943. As a "conscript" he has to dig graves in Berlin cemeteries. Together with about 100 other "Eastern workers", Kudrenko lives in a forced camp run by the Protestant Church in the cemetery of the Jerusalem and New Church congregations, between Hermannstraße and Tempelhof Airport. In his diary, he notes day after day his view of life in the camp, the hard work, hunger and the daily threat of bombs and the Gestapo. Like most of the male former "Ostarbeiter", Kudrenko is interrogated after liberation and then incorporated into the Red Army to do his military service.

(Source: Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko, "Bist du Bandit?", Berlin: Wichern-Verlag 2005, p. 72)

-

25

April

25Wednesday, 25 April 1945

Garden Colony "Trinity": Liberation of Hans Rosenthal

On April 25, 1945 Soviet units reach the allotment garden colony "Trinity" in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg. For two years the 20-year-old Hans Rosenthal, later known as "Dalli, Dalli" quizmaster, has been hiding here. He survives the persecution and the war thanks to the help of the allotment gardeners Ida Jauch, Emma Harndt and Maria Schönebeck.

Hans Rosenthal grew up in a Jewish family in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg. As a child he experienced the growing anti-Semitic persecution by the National Socialism. Both parents died at an early age. Together with his brother Gert, Rosenthal was sent to a home for orphans and had to take on the name Hans Israel Rosenthal. On October 19, 1942, Gert Rosenthal is deported to Riga and shortly afterwards is murdered in the Majdanek concentration camp. Other relatives did not survive the Holocaust either.

Rosenthal is sent to a Jewish training camp (Hebrew: Hachshara) near Sommerfeld in Lower Lusatia, but after its being forbidden in 1940 he is sent to do forced labour as a gravedigger for the Neuendorf farm near Fürstenwalde. Later he has to work as pieceworker in a cannery in Berlin-Weissensee and Torgelow.

On 27 March 1943 he manages to escape. With the help of Ida Jauch, a non-Jewish friend of his mother, he goes into hiding in an allotment garden of the "Trinity" colony in Lichtenberg. The people living there are mainly people from modest backgrounds who, due to a lack of work and homelessness, had converted the allotments into modest accommodation. When the 58-year-old dies unexpectedly, Maria Schönebeck, a neighbour and friend of Jauch, takes care of the young Hans Rosenthals.

After his liberation in 1945, Hans Rosenthal trained at the Berlin Radio, where he worked as an assistant director. However, due to conflicts with the supervisory bodies of the Soviet-controlled broadcasting corporation, he moves to the western sectors in 1948 and joins RIAS. Here he became known to a large audience as an entertainer, especially with his quiz show "Dalli-Dalli", which was broadcast from 1971 to 1986. Only late in life does Rosenthal talk about his Jewish past in Germany. In 1980 his autobiography "Two lives in Germany" is published.

From the memories of Hans Rosenthal:

"In the last week of April, apart from the thunder of guns, I heard a sound that was new to me: a rattle that made the earth shake - tanks. Tank tracks, tank engines, dull impacts. It was not exactly singing in my ears. But it was the sound of freedom...

I left the arbour and ran, without further consideration for my situation, in the direction from which the rattle of the tank tracks came. I took cover behind a hedge. And then I saw the tanks coming, dirty, noisy monsters. One stopped next to me. I ducked. I saw the Soviet star on the tank tracks, very clearly...

Only later did I learn that behind such hedges Hitler's boys and men from the 'Volkssturm', the last contingent, had lurked and directed 'bazookas' against the approaching tanks...

I proudly put my 'yellow star' on my jacket and set out to meet the liberators. I was no longer afraid of Nazis, although the possibility of a counterattack still existed.""Just outside the Central Stockyard there was a Russian tank, its crew chatting away. Waving brightly, happy, I approached the tankers. One of them was Jewish. He greeted me warmly and spoke German with me. He and his comrades had to advance to the city centre in a few minutes, he said. Whether he would survive it, who would know. I shook his hand. "Massel tov," I said to him, "good luck."

(Source: Hans Rosenthal, "Zwei Leben in Deutschland“ (Two lives in Germany), Gustav Lübbe Verlag: Bergisch Gladbach, 1993, p. 87f.

-

26

April

26Thursday, 26 April 1945

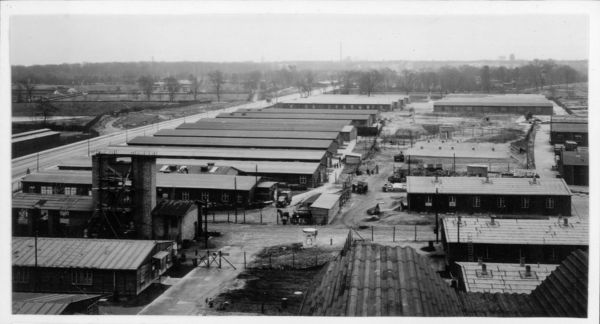

Tempelhof airport: forced labour for armaments

On 26 April 1945, Soviet troops advance in Neukölln to Hermannplatz and take Tempelhof Airport. Work on the airport grounds had only been completely suspended the day before. At the time of liberation, hundreds of forced labourers were still on the airport grounds. Until the end they had to work for the German aviation industry and the armaments production of the Nazi regime in the aircraft factories of the airport. Many of them lived in inhumane conditions until the end of the war, in several barracks camps on the grounds, fenced in by barbed wire. Others were housed in shared accommodation outside the airport.

The former forced labourer Karel Kincl remembers:

"For almost three weeks we slept only on the boards of the bedsteads, unwashed, unshaven, in work clothes, and in what was left of our clothes... Those who were prone to colds naturally got fever, inflammation of the respiratory tract and similar diseases."

They all worked under extreme pressure in the production of "Deutsche Lufthansa" and "Weserflug". For the Western European forced labourers the day and night shifts usually lasted 12 hours, for the deported "Eastern workers" up to 36 hours. Gestapo interrogations and beatings were the order of the day.

At the end of 1943 heavy bombing raids destroyed many barracks and part of the old airport building. In the night from 26 to 27 April 1945, the exploitation of the forced labourers in Tempelhof came to an end - but almost all of them now faced new challenges: the search for food, water and safe sleeping places. Quite a few of them set off on foot on their way home.

Since the 1990s, the history of forced labour at Tempelhof Airport has been dealt with by civil society initiatives. For some years now, archaeological excavations have also been taking place on the site. This is one of the topics covered by the new temporary exhibition of the Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre "Exclusion. Archaeology of the Nazi Internment Camps“.(Source: Karel Kincl, letter to the Berlin History Workshop; Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre , Collection Berlin History Workshop)

- 27

-

28

April

28Saturday, 28 April 1945

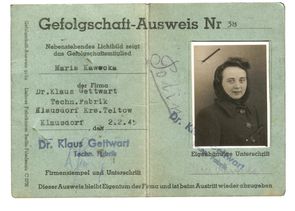

"On April 28, the front passed through Klausdorf": Maria Kawecka

"The Germans had an air-raid shelter we weren't allowed to use. I remember on April 28, when the front was next to us and the shelling from both sides continued, I hid in this air-raid shelter with two other colleagues out of fear; but after a few minutes we were discovered and we were thrown out. We had to find some kind of shelter under this fire. We discovered a hole, dug in the ground, in which we spent the whole night. And in the morning, the Russian troops were already there."

Maria Kawecka was born in 1918 in Lewiny, Poland, 40 km from Łódź. As a result of the occupation of Poland in 1939 the family was driven from their farm in Piotrów. In April 1942 the Germans deported the 24-year-old Maria, her two brothers and her parents. Kawecka had to help out as a nanny for three months with a gardener in Güstrow. She was able to return to Łódź, but was arrested again on 17 November 1942 during a raid on a tram.

Kawecka was deported to Berlin-Reinickendorf (Walderseestr. 21). She had to work for AEG and for the company Dr. Klaus Gettwart (Köpenicker Straße 50) in the production of aircraft and submarine parts, among others. In order to escape the ongoing air raids in Berlin, she tried to flee to her cousins on the countryside in summer 1944. In the S-Bahn she was controlled by policemen. Her documents revealed that she had left her workplace without permission and was travelling illegally on the S-Bahn.

The Gestapo sent her to the Gestapo " Arbeitserziehungslager“ (Work Education Camp, AEL) Fehrbellin. There Kawecka had to do hard physical labor in a bast fiber factory for three months. Hunger and maltreatment were the order of the day. When she was sent back to her workplace in Berlin after 3 months she weighed only 28 kg. None of the other forced laborers recognized her.

During an air raid in November 1944, Dr. Klaus Gettwart's factory was severely damaged and production was then transferred to Klausdorf. Here, Kawecka used her function as a materials tester to sabotage the armaments production. Maria Kawecka worked in Klausdorf until the liberation in April 1945.

(Source: Interview Ewa Czerwiakowski with Maria Andrzejewska, née Kawecaka, Łódź, 22 August 2004. Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre, Berlin History Workshop Collection)

-

29

April

29Sunday, 29 April 1945

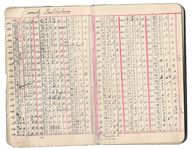

Emil Hermann GmbH & Co KG: Exemption Gerardus van der Broek

Emil Hermann GmbH&Co KG: Exemption Gerardus van der Broek

While the Rotes Rathaus ("Red City Hall") is already being stormed in the city centre, Soviet troops in northwest Berlin are advancing on the ruins of Charlottenburg Palace and occupying the Jungfernheide S-Bahn station. At Saatwinkler Damm 42/43 the war ends for the Dutch forced laborer Gerardus van der Broek. He had spent the last nights here in the factory of Emil Hermann GmbH & Co KG. His accommodation at Kreuzberger Obentrautstraße 33 was no longer accessible due to the fightings.

Born in 1922 in Delft in the Netherlands, van der Broek was conscripted to Berlin in May 1943. He is first sent to the Rehbrücke transit camp in Potsdam. The authorities assign him to work at the Daimler Benz AG plants in Berlin-Marienfelde. Here he lived in various accommodations, tents and barracks. In August 1943, after an air raid on the camp, van der Broek tries to escape but is apprehended in Leipzig and has to return to Berlin.

During an air raid in November, the camp of the Daimler factory is completely destroyed. Van der Broek now has to work in the office of Emil Hermann GmbH, founded in 1855 as a "colonial product trading company" at Saatwinkler Damm. He lives in an apartment of the company in Obentrautstraße. The administration of Gedelag AG (Association of German Food Wholesalers) is also located here. Van der Broek gets to work by public transport.An interesting contemporary historical document is van der Broek's notebook from the time in Berlin. From May 1943 to the beginning of April 1945, he documents the exact dates of air alarms and attacks, as well as all parcels received in Berlin and the loss of personal effects after bombings.

After returning on foot, Gerardus van der Broek reached the Netherlands on 16 June 1945. Three days later he returns to his home town of Delft.

(Source: report by Ton van der Broek)

-

30

April

30Monday, 30. April 1945

Warsaw Street: Liberation of Zenobius Gorzkiewicz

"In April we withdrew to Berlin with our guards. Not far from the Warsaw train station we were detained in the courtyard of a large apartment building... We were ordered to hand over all documents, letters and photos, even the badges with the letter "P"... Then they threw everything in one pile and set it on fire. We were led to an air-raid shelter ... Some Germans asked us to give them civilian clothes.

On April 30th, we could see through a crack the Soviet soldiers marching in. There were some among us who spoke Russian. We immediately raised a white cloth. Then some Soviet soldiers ran towards us and ordered us to come out one by one with our hands up. Our interpreters said there were about 300 of us. One of the officers put together a special platoon and ordered in Russian that Poles and other prisoners should line up on the right side of the yard and Germans on the left. When everybody left the bunker, they shot the Germans in front of us..."

Background:

Zenobius Gorzkiewicz was born on February 1, 1929 in the village of Grodzisko,

Voivodship Łódź. During the German occupation, Gorzkiewicz's family was active in the underground, at the junction between the Generalgouvernement and the territories attached to the German Reich. As a 13-year-old, Gorzkiewicz was captured in a tram during a raid in June 1942 and taken to a Gestapo prison. Three days later the Gestapo deported him to the German Reich together with other prisoners. He is first taken to a transit camp in Frankfurt (Oder), then to Wildau. Here, Gorzkiewicz has to work in the Schwartzkopff company's tool depot for the production of armaments. Later he is employed as a turner. The company's camp is surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers, armed guards guard the entrance. The rations and medical care are catastrophic. Gorzkiewicz must wear the "P" badge on his clothes. In early 1945 Gorzkiewicz is taken away by the Wehrmacht and forced to build trenches and anti-tank barriers. He is transferred to Seelow where, in April 1945, he is forced to supply the German soldiers in the trenches with food under constant fire at the front.(Source: Letter from the former Polish forced labourer Zenobius Gorzkiewicz dated 05.02.1998 and interview dated 21.08.2001 © Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre, Berlin History Workshop Collection.

-

1

Mai

1Tuesday, 1 Mai 1945

Potsdamer Platz: Waiting in the S-Bahn tunnel

In the days from April 28 to May 2, 1945, chaotic scenes take place in the north-south tunnel of the Berlin S-Bahn, between Friedrichstraße and Anhalter Bahnhof. During the last days of the war, thousands of Berliners had sought shelter in underground S-Bahn and U-Bahn tunnels from the ongoing fighting and air raids. So did numerous forced laborers, such as the Jewish forced laborer Walter Frankenstein or the French forced laborer Marcel Elola. Trains have not been running here for a long time and some of them served as makeshift hospitals. People crowded the platforms of the stations.

From Saturday, April 28, 1945, hundreds of people were also in the Anhalter Bahnhof. Catastrophic conditions prevailed. On May 1, at 9 o'clock in the morning, an SS guard appears and begins to drive people through the tunnel towards Potsdamer Platz.

A woman from Berlin reports: "When we reached the Potsdamer Platz station, the train [of people] had already thinned out. In the dark we stumbled further over the sleepers. Many fell and broke their arms and legs. They remained lying there helplessly. For a long time we could still hear their desperate cries... Then an SS man shouted: 'Foreigners, step out to the right. A shiver went down our spines. Some of the foreigners we tore into our ranks. The others stayed behind. The sound of gunfire that then echoed behind us gave us enough information about the fate of those left behind."

At the Friedrichstraße S-Bahn station, the group is driven into the underground tunnel in the direction of Stettiner Bahnhof (now Nordbahnhof). There they chase the people onto the street. The Berlin woman further reports that "the artillery fire was roaring at full strength. I staggered forward as if stunned. Hundreds of us were blown to pieces... It didn't want to be night, the burning sky over Berlin was so blood-red.

On May 2, 1945, a powerful detonation destroys the ceiling of the tunnel under the center of Berlin, exactly at the point where the S-Bahn passes under the Landwehrkanal. At the Friedrichstraße S-Bahn station, the water also overflowed the U-Bahn tunnels and flooded large parts of the Berlin tunnel system. It is estimated that between 800 [sic] and 15,000 people died. Among them probably also numerous forced laborers.

(Report by an unknown Berliner in the Berliner Zeitung of June 11, 1945, "Wettlauf mit dem Tod", sources: "Die Befreiung Berlins 1945. Eine Dokumentation, DVW, Berlin 1975, p. 135f. and article by Sven Felix Kellerhoff, Welt-Online of May 2, 2015)

-

2

Mai

2Wednesday, 2 Mai 1945

While the fighting in Berlin continues, the German General Helmuth Weidling begins in the early hours of the morning to draft the surrender order. From noon on May 2, loudspeaker vans each with one Soviet officer and one German military man will drive through the city to announce the surrender order. In the cellars of the Reichstag, fighting continues until 1 pm. From about 5 p.m. on, all fighting in the city ceases.

The exploitation by the National Socialist regime ends for about 370,000 forced labourers in the entire Berlin area - civilian deportees, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates. Quite a few of them are still at their workplaces at this moment. Some had already fled the camps in the days before or were hiding in the city. Others waited in the camps, their workplaces had not been accessible for days.

The condition in which the Soviet units find the forced labourers varies considerably. Those who were used in agriculture or in the service sector are usually a little better off than their comrades in arms industry. The liberated concentration camp prisoners are in a particularly bad shape.The enormous number of liberated forced labourers confronts the Allies with enormous challenges. In the next days and weeks, many of them set off for home on foot or with the help of various carts. Others make their way to the Displaced Persons Camps, which the Allied military administrations are setting up throughout the city. Return transports are organised from here. Yet others stay in the city, not knowing where to go.

For while some people experience this day as liberation, others shy away from returning home. They fear to be branded as traitors or suspected of collaboration because they have worked for "the enemy". Once back home, most former forced laborers will not talk about their fate for decades.

-

3

Mai

3Thursday, 3 Mai 1945

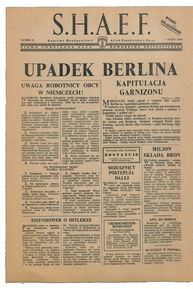

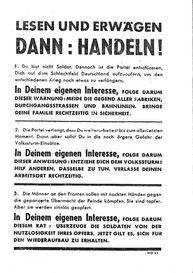

"Berlin is falling." Instructions for "foreign workers"

"Berlin is Falling", leaflet of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the highest headquarters of the Allied Forces in Europe, dated 3 May 1945. In the column on the right are "10 Commandments for "Foreign Workers" in Germany. Such as: "Stay in place. Protect yourself as far as possible - but not near military targets. Expect the arrival of the Allies." Or: "Unite - choose leaders for each small group of the same nationality."

With such measures, the Allies tried to prevent chaos and looting during the last days of the war and immediately after the capitulation and to organize the quickest possible repatriation of the liberated forced laborers to their countries of origin.

This leaflet was dropped and distributed in German, Polish, French and English.

- 4

- 5

-

6

Mai

6Sunday, 6 May 1945

Berlin Buchholz: Józefa Irena Łyskanowska-Kuncewicz

"The time of liberation was the worst for me. I had no shelter, nothing to eat, I was afraid to go out into the streets where shootings were still going on and there were loads of Soviet soldiers...

I stayed in contact with the [German] family where I had worked, i.e. the Pieel family in Buchholz. After the liberation I decided to visit them. When the boss heard that I had no shelter and nothing to eat, she immediately suggested that I move in with them. Her daughter let me have her room. So I was safe and no longer hungry."

Memoirs of the former Polish forced labourer Józefa Irena Łyskanowska-KuncewiczJózefa Irena Łyskanowska-Kuncewicz is 17 years old when she is deported from the Polish village of Chabielice, at Łódź, to Berlin in March 1940. In the Buchholz district of Berlin she had to work for the Otto Pieel gardening company, first in the greenhouse and later in the fields. In summer, working hours often last from 5 a.m. to 8 p.m. in the evening. Józefa Kuncewicz is accommodated in the Pieel family home, where she is treated comparatively well. When winter sets in and there is not much work left in the plant nursery, Józefa Kuncewicz is sent to a farm in Berlin-Buch. Here she has to do heavy piecework on a potato field. When Kuncewicz appears at the employment office a short time later to change her job, the police arrest her. She spends two weeks under terrible conditions in the Spandau prison.

In winter 1943 Kuncewicz is transferred to a camp in the Tempelhof district. She now works in Schöneberg for the Siemens company. She arrives at work together with the entire shift group in the tram. In Tempelhof, Józefa Kuncewicz experiences a heavy air raid which also hits her camp. She remembers: "Our camp leader said: 'You Polish women are in God's favor.' For only our barrack remained unharmed. A bomb fell through the roof into my colleague's bed, but thank God it was a dud."

When parts of Siemens production are moved to Zittau because of the air raids, Kuncewicz is sent to the Siemens production site at Grüntaler Strasse 63 in the district of Gesundbrunnen. Here she experiences the end of the war in May 1945. A few days later, when she visits the Pieel family home, she finds shelter there, helps in the garden and in the household. In June 1945 the Soviet command in Berlin summons Kuncewicz and sends her back to Poland. Here she met her family again.

(Source: Letter from the former Polish forced labourer Józefa Irena Łyskanowska-Kuncewicz to the Berlin History Workshop, January 24, 1998) -

7

Mai

7Monday, 7 May 1945

Famine: "Don't let them kill you, the Germans are vicious"

In the days shortly before and immediately after the capitulation of the Reich capital on 2 May 1945, there were repeated burglaries in cellars, apartments or food depots by liberated forced labourers. As was to be expected, violent acts of revenge against Germans were not absent. The former Polish forced labourer Aleksandra Reniszweska recalls:

"A friend and I drove to the boys in the camp. We couldn't return because the Soviet troops were advancing very quickly. On the roll call square the boys hanged the camp commander, who was allegedly very mean. When the Germans began firing from the other side of the Spree in the direction of Soviet scouting troops, we feared they might retake this shore. If they had seen the hanged camp leader, they would surely have shot us all."

Often the former forced labourers reacted with such actions to the massive repression to which they were exposed throughout the war. Particularly in the last weeks of the war, random excesses of violence against forced labourers and targeted executions by SS units had also increased in Berlin. As usually, the liberated persons did not proceed indiscriminately, but sought out superiors, foremen or camp leaders.

The catastrophic supply situation also prompted many liberated men to break into storage depots or apartments. The former Polish forced laborer Kazimiera Czarnecka reports:

"A strange thing happened. The uniformed camp commander Zielke no longer exists, there are no guards... The kitchen remains closed and no food is handed out. We are hungry. Someone comes with the news that the men are breaking the locks to the food storage and that there is something to eat. In the storage there were bags of semolina and sugar. They were delicacies. During our entire stay in the camp we had never received an ounce of sugar."

Liberated Italian forced laborer Ugo Brilli also remembers the days immediately after the war:

"There was chaos... the Germans ran away. We went to the cellar to find food... The Russians gave us three days' green light - you can do whatever you want, but be careful, don't get killed, because the Germans are vicious."

The perception of the "plundering and marauding foreigners" plays a major role in the German perception of the first days of May, which is still significantly influenced by Nazi propaganda. Later on, it also often shapes the memory of the spring of 1945. Such reports do not, it seems, come as a surprise to the German public. After all, they covered up the guilty conscience about the brutal treatment of many forced labourers - especially those from the Soviet Union.

This often repeated narrative, however, ignores the fact that, on the whole, the crime rate of the post-war days was not much higher among displaced persons than among Germans. For the latter increased significantly after the war.(Sources: Letter of 17 November 1997 from the former forced labourer Aleksandra Jelinek, née Reniszewska, to the Berlin History Workshop and interview with Ugo Brilli on 22 April 2012 © Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre; Volker Ulrich, "Eight Days in May," Munich: C.H. Beck, 2020)

-

8

Mai

8Tuesday, 8 May 1945

Surrender: "Go home"?

The Soviet war correspondent Lew J. Slawin remembers the moment of the arrival of the German and Soviet delegations to receive the declaration of surrender:

"An unexpected encounter. A long train of foreigners liberated from Hitler's concentration camps. Over carts, bicycles, strollers in which the liberated carried their belongings, flags of all nations were waving: Yugoslavian, Italian, French, Dutch and others. On one post there is an arrow pointing the way and the inscription in all languages: 'To the collection point of Soviet and foreign nationals'. The German delegates look away. ... They look down in vain, or blow their nose eagerly to avoid the eyes of the people through their handkerchiefs. ... I can't say that the Berliners make sad faces. Rather, they express a certain satisfaction at the sensational spectacle."

With the capitulation of the German Reich on 8 May 1945, the Allies were confronted with huge numbers of so-called Displaced Persons - people of other nationalities who wanted to return home or had become homeless as a result of the war. At the end of the war in Berlin alone, there were about 370,000 forced labourers from all over Europe.

Even when the war was still in full swing in the city, numerous liberated forced labourers mingled with the refugees in order to return home or to the next section of the front.Now, with the final end of the war on May 8, 1945, countless people set themselves in motion to return to their countries of origin. DPs from Western Europe in particular are trying to make their way on their own. Others wait in the ruins of the city or in improvised camps for onward transport to their homes with the support of the Allies. Most of the Displaced Persons (DPs) reach their countries of origin during the summer. In August 1945 there were still about 23,000 foreign citizens living in Berlin.

In various countries the forced labourers are suspected of having collaborated with the Germans. The liberated "Eastern workers" and Soviet prisoners of war have to pass through filtration camps of the Soviet intelligence service. For many of them the war ends with their deportation to Soviet penal camps.

It is not uncommon for former forced labourers from Poland to refuse to return because they reject the new communist regime or because their hometown is in eastern Poland, which was annexed by the Soviet Union.(Sources: Lew J. Slawin, " The Final Days of the Third Reich, Berlin: Lied der Zeit Musikverl. 1948, p. 46 ff.; Helmut Bräutigam, "Forced Labour in Berlin 1938-1945", publication of the Berlin Regional Museums Working Group, Berlin: Metropol, 2003)

-

9

Mai

9Wedneday, 9 May 1945

Going home? - Interim camp Berlin-Biesdorf

"People had brought in sewing machines from surrounding houses, with which they made national flags of their countries of origin from scraps of fabric." (Memories of Werner Sedlick, a resident of the area)

Werner Sedlick is 14 years old when the war ends in Berlin in spring 1945. He lives with his family in a house in Berlin-Biesdorf. His father works as a nurse at the Wuhlgarten Hospital (later Wilhelm-Griesinger-Hospital). In May 1945, a car repair shop is set up in a barrack opposite the family home by Soviet soldiers, who soon maintain friendly contact with the family. Not far away, a "wild" transitional camp for liberated forced labourers is established:

"A few weeks after the end of the war, a collective camp for liberated fourced labourers was established on the open field between Grabensprung and Köpenicker Straße, north of the railway embankment. More than 1,000 men and women lived there under the most primitive conditions for about 2-3 months. Italians, Poles and so-called Eastern workers...

Since my father was a nurse, it turned out that he often cared for the sick and injured in the camp. Now and then he took me there as a support. Previously brutally exploited, the liberated forced labourers, regardless of their origin, were now very grateful for interpersonal assistance ... Most of the former forced labourers lived in tents and huts they had built themselves. The materials and facilities for this were taken from surrounding gardens and apartments. The people used the nursery across the street to provide their necessities. Living together there was also characterized by frequent scuffles. Again and again there were also injured people.

The liberated foreign workers were transported home from the collection camp. Most of them were taken on horse-drawn carts in the direction of Kaulsdorf station. The transport was probably organized by Soviet soldiers."The former French forced laborer Jean René also remembers such a camp:

"May 9: We don't know what will happen next. At the moment we are in Biesdorf... I didn't sleep much last night. The nights are too cold to sleep in the open air, so we have built a small barrack... There are about 20.000 of us and more are coming from all sides. It'll be a temporary camp. People from all over the world to be divided up. This afternoon we received official word that the war is over... If only an order could be given that we can leave this unlucky country."

(sources: Interview with Werner Sedlick, March 17, 2020; Jean René and Hervé, "A pawn in the turmoil of war. Diary of a prisoner of war, Saint-Denis: Edilivre, 2017)

Liberated forced labourers from different countries of origin march through Berlin between Soviet tanks, cheering and with loaded carts © history-vision / Vistarena -

10

Mai

10Thursday, 10 May 1945

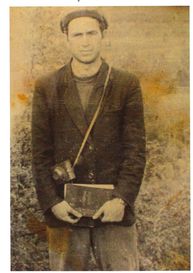

Lichtenberg: Theodor Wonja Michael

"The Soviet officer flipped through his workbook, looked at me and asked me what I was doing here in Germany. I was startled and explained that I was born here after all. My father had come to Berlin after Cameroon had become a German colony... Whether I had worked for the Nazis was the next question. I answered truthfully that as a foreign worker I had been conscripted for war service, that I had been accommodated here in this camp and had worked in an armaments factory... The conversation had developed into a strict interrogation, which became unpleasant for me (...) It was so unlikely that a black German would still be alive after the war that I was suspected of collaboration... 1945 was a terrible year, the hardest of my life: What would you answer if you were accused of being alive? As the saying goes, I was always caught between two stools".

Theodor Wonja Michael was born in Berlin on January 15, 1925, the youngest son of Theophilius Wonja Michael from Cameroon and his German wife Martha (née Wegner). His mother died just one year after the birth. When his father also died in 1934, Michael was only 9 years old. He grows up under partly miserable conditions with foster parents who want to make profit out of him and let Michael perform at "ethnographic shows".

When Berlin classmates rave to the 9-year-old about the meetings of the NSDAP junior staff organization "Jungvolk", he too wants to become a member. To his surprise he is rejected and sent away. That's when Michael senses for the first time that he doesn't belong, he remembers later. In 1939 he finishes elementary school, but cannot start an occupational training because of the discriminating Nuremberg racial laws.

To ensure his survival, Theodor Wonja Michael tries from now on to remain as invisible as possible, constantly accompanied by fear of arrest and forced sterilization: "That was the important thing for us during the Nazi era: not to stand out. I did everything I could to keep a low profile." So he worked as a doorman in a hotel in the meantime, but was dismissed due to a complaint of a guest "about his skin colour". Michael's passport is also withdrawn and he is now stateless.

As an Afro-German, Theodor Wonja Michael experiences National Socialism as a time full of contradictions: "In 1943, after the proclamation of 'total war', anyone who could still carry a rifle was drafted. But I wasn't drafted and I can only say that I'm still grateful to God for that today.

In 1943, the 18-year-old was sent to forced labour. For the ammunition factory J. Gast in Lichtenberg he had to work in the armaments production from now on, 10 to 12 hours a day. As accommodation he is assigned to a "foreign labourer camp" at the Adlergestell. Since he only speaks German, the other forced labourers look at him suspiciously. With a lot of luck Michael survives several bomb attacks in the outdoors. As a so-called "foreigner" he is denied access to the air-raid shelter.

On April 20, 1945, Theodor Wonja Michael experiences liberation in the Lichtenberg factory. But once again he finds himself in a paradoxical situation, as the Soviet liberators first accuse Michael of collaboration with the Nazis.After the end of the war, Michael passes his Abitur and studies in Hamburg and Paris, among other places. Later he worked as a journalist and editor. In 1971 Michael began working for the German Federal Intelligence Service. He is the first black federal civil employee in the higher service. At the same time he is involved in the Afro-German community. Theodor Wonja Michael dies on October 19, 2019 in Cologne.

"The liberation is a sore point for me to this day. I must say that Germany was and is my home. And then you suddenly see your homeland broken and shattered. One is free oneself: that is wonderful! It's a wonderful thought to be free from the burdens that you had before. But is one really free?"

(Sources: Theodor Michael, "Being German and black. Memories of an Afro-German," Munich: DTV, 2013; interview by Corinna Spies with Theodor Michael, 23 March 2014; "Theodor Michael Wonja, dernier rescapé noir des camps de travail nazis, est mort," Le Monde, 25 October 2019; illustrations: private property)

- 11

-

12

Mai

12Staurday, 12 May 1945

Going home? Vasyl Timofeyevich Kudrenko

"I left the cursed, destroyed Berlin. I lived in this city for two and a half years. I was now part of a Soviet military unit. We were ordered to leave the city at 6:00 a.m. and head for the Oder. We were walking and escorting captured fascists. We walked from 6:00 a.m. to midnight. The day was hot...

Hundreds of Soviet planes could be seen in the sky, and next to us armoured vehicles and motorcycles were moving at lightning speed... We spent the night in a village. We were back on the road at 6:00 a.m. On the way our trucks caught up with us. We were allowed to get in and take a ride. So we reached our destination very fast...

Our unit was stationed in a village. I was exhausted after that unusually long march... After sleep, Subzov, Lieutenant of the guard, called me. He said: 'If you want, you can stay with us. You'll have to do everything you're told and just be a good guy. I replied, "Yes, Comrade Lieutenant." "Since then, I have been his aide."Vasyl Timofeyevich Kudrenko was 16 when he was taken from the Ukrainian village of Balakliya to Berlin in 1943. As a "forced labourer" he was forced to dig graves in Berlin cemeteries. Together with about 100 other "Eastern workers", Kudrenko lives in a forced camp run by the Lutheran Church in the cemetery of the Jerusalem and New Church congregations on Neuköllner Hermannstraße. In his diary, he notes day by day his view of life in the camp, the hard work, hunger and the daily threat of bombs and the Gestapo.

After his liberation by the Red Army on 24 April 1945, Kudrenko is initially suspected of collaborating with the Nazis as a traitor to his country. Like hundreds of thousands of other liberated "Eastern workers", he is initially subjected to interrogation by the Soviet secret service.

On May 25, he is ordered to report to the transit camp Töpchin near Zossen before returning to the Soviet Union. Here he learns that all former fellow inmates from the cemetery camp were called up for military service in the Red Army immediately after liberation.On June 1, Kudrenko is interrogated by a Soviet lieutenant in the Töpchin transit camp. In his diary he notes: "Today I was interrogated by a Leutnant who read my diary. He asked: 'In November 1944 you told German workers that Stalin was coming soon. The Gestapo knew that. "Why were you interrogated and not arrested? I affirmed: 'I was brought up in the communist spirit, a simple Soviet man, deported to Germany under duress. "My life was in danger. In Germany, I behaved as a true patriot. The lieutenant claimed I was lying."

(Diary, Saturday, June 9, 1945)Kudrenko manages to convince the lieutenant of his loyalty. Two days later, he's allowed to head east. By train Kudrenko reaches Rawicz in Silesia via Cottbus and Glogow. Here he has to face another interrogation in a Soviet transit camp. In the camp, all registered 1920-27 cohorts are assigned to agricultural work near Hermannstadt. Only on 29 August 1945 does Kudrenko receive his documents for the examination procedure and is sent home from Rawicz. He remains convinced of the "bright future of the Soviet Union".

On 16 October 1945 Kudrenko reaches his parents' house in Balaklija. This is also where his diary entries end. Most of his home village has burned down. Before the liberation, Kudrenko later recalls, he had not expected to return from Germany.

(Vasyl Timofeyevich Kudrenko, "Are you a bandit?" The Camp Diary of the Forced Labourer Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko, Berlin: Wichern-Verlag 2005, p. 132f.

-

13

Mai

13Sunday, 13 May 1945

Pertrix battery factory: return to Poland

"There was a whole group of Poles, and we, that is my Papa and I, joined them. We walked, not knowing the way. We were hungry and exhausted. It was very important for us to leave Berlin and the German country in general as soon as possible. We arrived in Poznan, where a train with many wagons stood at the station. The Russian military took various machines from the factories and took them away to Russia. They accepted us in a wagon which already contained a dozen soldiers who were supposed to guard the machines... Fortunately we arrived in Warsaw. Only ruins remained of Warsaw, there were no streets, no houses. There we found out that the Germans had signed the surrender."

(Memories of the former Polish forced laborer Janina Łyś)Janina Łyś was born on 3 December 1923 in Mokre near Zamość (today eastern Poland). She spent her childhood in Lublin, where she attended a private grammar school. In the summer of 1939 her father is drafted into military service. He returns at the end of 1942, just as the German authorities are beginning to deport the non-Jewish population of Zamość and the surrounding area to Germany as part of the "General Plan East".

Janina and her parents are deported to Germany for forced labour. In the Wilhelmshagen transit camp, the family is assigned to the Pertrix battery factory (Quandt Group) in Berlin-Schöneweide. From now on they are accommodated in a barrack in the Adlershofer Straße (today: approximately Bruno-Bürgel-Weg 84). Janina Łyś has to work daily from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. on a conveyor belt, where she fills electrolyte into battery cases. The work is extremely dangerous and she is refused working gloves. Janina is trained by a Berlin Jewish woman who disappears a few weeks later. The Poles from the region Zamość had been brought into the factories as replacements for German Jewish women deported to the death camps.The food situation in the camp is very bad. But sometimes Janina can buy some vegetables from her low wages. During air raids, the forced labourers in the camp can only protect themselves very poorly in splinter protection trenches. Still in 1943 Janina's mother is sent back to Poland because of illness.

Shortly before the end of the war, at the beginning of April 1945, Janina Łyś is abused by a master craftsman who threatens to report her to the Gestapo for refusing to work. She resists and warns the man to report him to the Russians after the Soviet invasion. This threat apparently has an effect and the master refrains from it: The fear of the approaching Red Army is already very great among the German population in spring 1945. A short time later Janina experiences the liberation in Schöneweide.Some of the former forced laborers from Poland later report that in the spring and summer of 1945 they set off for home on foot, by bicycle or, with a little luck, on the back of a truck or freight train. Janina Łyś is one of them: Together with her father she now makes her way on foot to Poznań. From there they travel by freight train via Warsaw to Zamość. However, quite a few Poles refuse to return: they reject the new communist system in their homeland or do not want to return to the Eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union. While the majority of the Displaced Persons (DP) from the Soviet Union are still repatriated in 1945, some of the liberated Poles try to emigrate to North America. Many reach West Germany as "homeless foreigners".

Janina Łyś marries in 1945 and lives with her husband and children born in 1948 and 1954 in Danzig and Warsaw. As a result of her work at Pertrix, she suffers from health problems throughout her life.

(Sources: Memorial report by the former Polish forced labourer Janina Łyś of 9 July 2014, Nazi Forced Labour Documentation Centre; "Marked forever. Die Geschichte der 'Ostarbeiter', published by Memorial International, Moscow and Heinrich Böll Foundation, Berlin, Ch. Links Verlag: Berlin 2019)

- 14

-

15

Mai

15Tuesday, 15 May 1945

Alexanderplatz underground station: Marcel Elola

"After this exhausting day we returned to our accommodation, ate from the heart and then fell into a night's sleep. The next day the Russians came back and told us that they were looking for volunteers to fight against the Nazis. After all we had known about this army ... none of us volunteered. This was certainly the reason why the Soviets decided to prepare our departure. During the day, guards were posted at all exits. Our departure for the Soviet Union was about to happen, but no one was aware of it. Had we known what to expect, many of us would certainly have made our way into the fields at night."

(Memories of the French forced labourer Marcel Elola)Marcel Elola is 21 years old when he is captured by the French police in Paris in March 1943 and handed over to the German occupying forces. As a forced labourer, he is first brought to Oranienburg, but he is lucky: as a trained butcher, he finds accommodation in a private business in Berlin-Schöneberg. Later he is assigned to an SS supply company, where he barely survives a bomb attack. Due to his work in the food supply, Elola has access to important food, which ensures his survival. Other forced labourers accuse him of collaboration with the Germans. After heavy bomb attacks, which destroy the camp, Elola can move into an apartment in the city together with other internees.

In mid-April 1945, Marcel Elola experiences the continuous bombardment of Berlin by the Allies at the Alexander Platz underground station. Hundreds of people seek protection on the platforms of the Berlin tunnel system. Here Elola observes how units of the SS and the field gendarmerie continuously check papers and lead deserters into the underground tunnel to be shot. Shortly thereafter, all "foreigners" have to leave the station and are led by armed SS units as a marching column through the city centre towards the west. Only when the guards run away the next morning does Elola realize that the Red Army is not far away. In a village just before Nauen he experiences the liberation: "Around 6 pm in the evening the Soviet flag with hammer and sickle is hoisted in the middle of the courtyard. With what is at hand, we make a French flag. The soldiers agree after a long back and forth to hoist it next to the Russian flag. A Pole must translate."

The Red Army soldiers now use Elola and the others to level an airfield in a nearby field. The work is hard and exhausting. A few days later, they're put on trucks. Bumper to bumper they drive in a long train towards the east. On the loading platforms sit Italians, Dutchmen, Serbs, Poles and some Frenchmen. Also former Soviet prisoners of war are among them. When after 1,200 km the convoy reaches a camp just before Odessa, Elola decides to flee. Together with two Dutchmen and two Germans he manages to bypass the guards. They can persuade the German driver of a supply truck to take the group westwards. On the morning of 19 May 1945 they reach Fürstenwalde. Elola returns to Berlin to find a way back to his home from there. On June 6, 1945, he reaches the Gare de l'Est station in Paris. "Later," Elola recalls, "we learned that the other French who did not flee the Odessa camp did not return from the USSR until many years later."

(Marcel Elola: "I was in Berlin". A French forced labourer in Germany 1943-1945, Berlin: Divers Gens/Edition Berliner Unterwelten, 2005, p. 96)

- 16

-

17

Mai

17Thursday, 17 May 1945

"Test and Transit Camp": Return to the Soviet Union

Immediately after the capitulation of Nazi Germany on May 8, 1945, the Allies quickly succeeded in securing a basic supply for the countless Displaced Persons (DP) in Berlin. A speedy return to their home countries was also to be guaranteed, with thousands of former forced laborers being returned to their countries of origin almost daily until late summer 1945. In August 1945, only just under 23,000 foreign citizens were still living in Berlin.